The Unseemly silence of crashing waves

(ON BIRTHING WHILE BLACK)

by Sandra Ojeaburu

As the United States encounters a reawakening in which protestors line the streets decrying the long injustices and inadequacies in food access, criminal justice, jobs and healthcare, the continuous silence around the distinct inequities that Black women face is deafening. Moreover, the silent suffering of Black mothers nationwide, in response to their children’s deaths, is made invisible as many mourn their worst nightmare that comes true all too often.

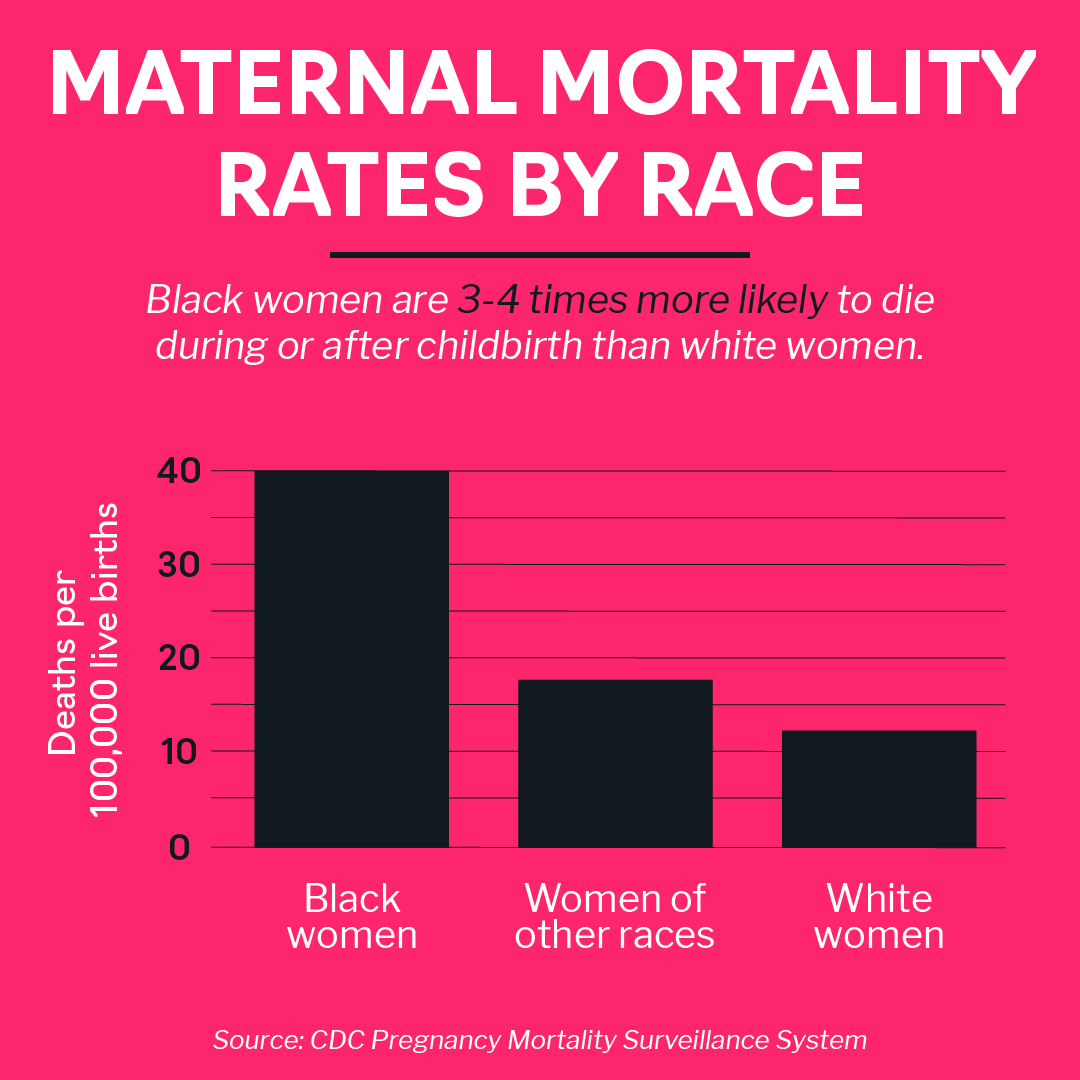

In the past year, healthcare workers, and activists have turned a mirror on Black maternal health. Using statistics to call attention to the dismal facts of the matter, they conclude that Black women are dying. When asked for solutions, many called for implicit bias training in hospitals. In response, Black birth workers and mothers alike who have been calling attention to this injustice for decades, saw the way their grief became treated as an exhibition—acknowledged, but the gaze quickly averted. With minimal structural or sweeping legislative changes, this terrifying and pervasive problem was vocalized as a burgeoning focus, and even yet, rendered invisible. What these analyses and recommendations failed to mention is the inequities in the way Black infants are born are tethered to the way thousands of Black Americans die—without justice.

“The recent reinvigoration of the Black Lives Matter movement and endless protests have highlighted the way Blackness has been condemned through assumptions of criminality. ”

The recent reinvigoration of the Black Lives Matter movement and endless protests have highlighted the way Blackness has been condemned through assumptions of criminality. For Black women, this label and perception is unique—misogynoir—an amalgam of sexism and racism that creates a distinct level of persecution that Black women face. While activists ranging from Sojourner Truth to Audrey Lorde articulate the specificity with which Black women face misogyny, Moya Bailey coined the term stating, “it’s such a specific denigration of black women, not other women of color, not black men." (1) During these times, many rightfully call for abolishment of the police, diverting funding to community-based programming, and this same approach must be applied to Black women’s reproductive justice and mothers’ birthing landscapes. Birth must be looked at as a reflection of environment, communities, living situations, food access, housing settings, and psychological well-being. The very fabric of maternal health necessitates structural changes to healthcare delivery and a psychosocial approach to care. Simply, maternal health must be provided at the intersection of social care and medicine.

The reproductive justice movement first espoused this intersectional foundation of healthcare. Black and Indigenous women have led the fight for reproductive justice for the well-being of each other and their right to have children or not. Motherhood is a unique time in which in which structural inadequacies regarding care come to bear on the bodies of expectant mothers. A crucial period in which inadequate healthcare access, and disparate food access render many mothers at risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, preeclampsia, and other conditions that increase the Black maternal mortality rates. Yet, statistics on maternal health do not divulge that the ramifications of structural inequality which impact Black mothers are continuous—they exist before pregnancy and long after a mother gives birth, they follow a continuum. In fact, the difficulties of motherhood are only exacerbated by the unspoken, coded fear that comes with being a Black mother in America. It’s knowing that the fears of childbirth itself are the start of constant underlying fear that result from bringing a Black child into a society that challenges their right to exist—to matter.

“The mother that chooses to bring a child into this life traverses the all too familiar terrain of motherhood, a time riddled with waves of terror and a sense of stress that accompanies each hospital visit. ”

Today, the experience of mothers consists of 2 waves, first, that of COVID 19 infection rates that continue to rise in Black communities, exposing the structural inequities in labor and healthcare access; and second, a wave of anger and anguish that sweeps across the country as rates of police brutality do not cease and the virus of racism continues to have a stronghold on our nation. In both of these waves, many realize the land of the free truly has never been yet. Yet, to the Black woman, this has always been the reality. The mother that chooses to bring a child into this life traverses the all too familiar terrain of motherhood, a time riddled with waves of terror and a sense of stress that accompanies each hospital visit. Unearthing these fears and acknowledging the chronic stress that these two waves bring is of paramount importance in addressing Black maternal mortality and inequity in Black mothering.

New data indicates that COVID-19 mortality and morbidity rates are higher in Black and Latino populations. African American deaths from COVID-19 are nearly two times greater than their proportion of population, while in 4 states, the rate is 3 times greater than that of white individuals. (2) Structural racism and consequently, racial disparities are predictors of complications from coronavirus and complications in childbirth. Black individuals have higher rates of pre-existing conditions such as respiratory illnesses that make them more immunocompromised and susceptible to covid-19 infection. In addition to limited healthcare access, Black people are more likely to live in densely populated, multi-generational living conditions due to institutional racism in the form of housing segregation, redlining, and generational economic inequality. Finally, many Black individuals are essential workers that are exposed to the virus at higher rates. Moreover, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes have been identified as risk factors for death from COVID-19. These stressors that are risk factors for covid-19 are also risk factors for maternal morality for Black mothers.

COVID-19 brings a distinct set of challenges for Black expectant mothers that try to maintain this necessary continuous support. In addition to the risk of the coronavirus complicating pregnancy, the disruption in routine prenatal doctor visits as well as the delay in seeking care during the pandemic has decreased the quality of care birthing Black individuals face. As telehealth increases in use, this is often insufficient for expectant mothers, especially those with communication inaccessibility, limited Wi-Fi or lack of broadband connection altogether and finally, pre-existing conditions such as hypertension. Finally, evidence indicates that continuous labor support during pregnancy, childbirth, and postnatal care improves birth outcomes, especially of women of color. Yet, social distancing restricts these home visits and elements of support. Similarly, these stressors increase levels of chronic and toxic stress that sustain health inequities in Black populations. Simply, the medical and familial support that expecting mothers need in these times have been stripped away.

“To birth in the shadow of racial prejudice, food insecurity, and economic immobility is to face the exacerbated effects of structural racism and systemic genocide.”

Worse yet, birthing while Black highlights a complexity that intertwines these waves of Covid-19 and police brutality, into compounding crises that only undercuts and barrages women’s psyches. Claudia Rankin put the underlying fears mothers face powerfully, she wrote, “the condition of Black life is one of mourning.” (3) To birth in the shadow of racial prejudice, food insecurity, and economic immobility is to face the exacerbated effects of structural racism and systemic genocide. On top of the constant fear of being subject to unwarranted searches, stops, and harassment by police, is the fear of having your child be subject to the same discrimination, and fear that threatens your very existence. The families of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and those whose names go unspoken every day know this well. Their mothers bear a unique burden and grief that one can barely imagine, especially as many victims of police brutality most do not get the justice they deserve. How can we link the justice we seek against police brutality with reproductive justice to birth in power and safe, healthy communities?

Reproductive justice outlines the need for acknowledging Black reproduction in America in the aftermath of slavery, discriminatory practices, and systemic racism, seeking solutions through decolonized birth methodologies. “Decolonization” is the process by which an individual or group rejects the definition of itself as marginal in relationship to a conceptual norm that has been forced upon them from the outside. Birth in the United States for African American women has historically been under the auspices of control and restrictions. The landscape of birth for Black mothers sits, as Saidiya Hartman has coined, in the “aftermath of slavery.” (4) In many cases, the healthcare system and public health system has policed Black mothers and instead of care, provided methods of surveilling their care, with the intent to “rescue” Black children, form the grips of their mothers. The reproductive justice movement acknowledges this approach as the product of misogynoir and that Black birth in the United States must be viewed through the lens of control and in the wake of colonialism. Black women’s bodies have been a site of colonization and the legacies of this continue to bear repercussions in the present day. The key tenant of dismantling injustice is analyzing legacies of reproductive control and structures that continue these racist notions in the healthcare system.

Historically, Black reproduction in the United States for decades was treated and viewed as labor production. Before slavery was abolished, Black enslaved women’s reproduction was surveilled and monitored, as many were forced to have children to increase plantations’ labor force. When slavery was abolished, Jim Crow era was characterized by a restriction and sterilization of Black reproduction and continued experimentation. The practice of gynecology and maternal healthcare were predicated on these notions of reproductive surveillance, nonconsensual experimentation, and unwanted sterilization. Countless instances of medical experimentation on Black individuals, indigenous peoples, and prison inmates. For example, the forced sterilization was so ubiquitous in Mississippi that the term, “Mississippi appendectomies” was coined to outline the prevalence of this abuse of medicine.

Today, these practices of reproductive control, are manifested through inadequate dialogue and subsequent lack of support in the healthcare system. The limited time given in appointments and issues of limited healthcare access, food insecurity and previously discussed social determinants of health worsen birth outcomes for Black mothers. Moreover, even in public health, the trope of the “welfare queen” pervades the discourse within hospitals and labels Black mothers as irresponsible, and dangerous to their child’s well-being. In her ethnography, Reproducing Race, Anthropologist and law professor Khiara Bridges, describes the manifestation of this trope in the “wily patient” in a large public hospital in New York. (5) She outlines how too often, nurses and doctors judge Black mothers as selfish, especially those on Medicaid for having children when they do not have the means to care for them. This often, indirect, and insidious notion goes unacknowledged, but has ramifications that determine the care Black mothers receive. A decolonization framework acts to view these racist notions of reproduction as stressors that demand special attention.

“...too often, nurses and doctors judge Black mothers as selfish, especially those on Medicaid for having children when they do not have the means to care for them. This often, indirect, and insidious notion goes unacknowledged, but has ramifications that determine the care Black mothers receive.”

While a community-based approach to maternal health may be aspirational, in all practicality, what does a decolonized approach to Black maternal health even look like? In Mississippi, a burgeoning doula movement demonstrates that it requires a return to community and Black mental health as a site of resistance. Frantz Fanon first acknowledged the intergenerational trauma that impacts the health and the well-being of Black individuals. Almost 80 years ago, he suggested the biological groundings of toxic stress that affect Black peoples, especially expectant mothers today. (6) This acknowledgement of mental health as a core tenant in care can radically shift the focus of maternal care.

Similarly, we must analyze and problematize notions of Blackness in the healthcare system that contribute to the criminalization of Black and Brown peoples. Especially those that blame mothers, label many as selfish or monitor them as potential risks to their own children. The decolonization framework of approaching birth acknowledges the structural violence of the medical-industrial complex that has taken psychosocial support and caretaking from birthing and replace it with monitoring and risk- assessment.

Thus, a paramount pillar of reproductive justice is continuous support of mothers before, during and after childbirth. This movement combined with a framework on the decolonization of maternal healthcare acts to rupture the institutional racism that manifests in poor birth outcomes for Black women, within the healthcare system. It advocates for birth to be embraced with community-based, grassroots psychosocial support. For instance, the grassroots organization, the Mississippi Birth Coalition provides advocacy, midwives, and doula care embedded in community meeting spaces. The burgeoning doula movement in the state is both a healthcare and political movement that advocates for a return to traditional maternal health in prenatal and postpartum care that many mothers say was taken from them with the development of hospitals and public health.

The recent waves of protests signal that there is abundant opportunity to decolonize our healthcare system. Specifically, for maternal healthcare, this means placing funding, mental health resources and services in the hands of community supports and grassroots organizations that ensure communities are offered effective and culturally specific care. In the same way protests call for restructuring community funding and providing alternatives to policing, equitable maternal healthcare calls for restructuring locales of maternal care and birthing support. Simply, reproductive justice calls for governments to place money in childcare services, invest in birthing centers, expanding free support groups for women on Medicaid such as Baby Cafés, and finally focusing on mental health services that alleviate and give mothers resources to mitigate the effects of underlying toxic stress. Birthing support as a human right, offers a specific lens of justice that re-centers care in support/ partnership within communities of color. Recent legislation is beginning to provide increased support and services to women. The MOMMIES Act (7) introduced in 2019 used a community-based method of ensuring mothers are supported post-partum and the CARE Act (8) that helps deliver health care services to pregnant women and new moms. The legislative approaches to care acknowledge the need for community support and are supported by the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, which uses grassroots activism to promote structural change and begin to combat Black maternal mortality.

As a Black woman that is far from birthing a child herself, I think about what this shift in discourse and potential legislation mean for young Black women. It is the joy of looking in the mirror and knowing I have a greater diasporic community that despite all odds—unites. However, it also means seeing what is at stake. Every time I desire to go for my daily run, and my mother says, “be safe,” her eyes linger on my face longer than usual-- that is what Black mothering means. Those two words encompass so much and remind me that for Black peoples, safety is a privilege, not a given. It is an underlying fear that seems to be incessant, intolerable, and never ceasing. This fear often manifests itself in a refusal to go to a doctor or dentist checkup—her last checkups were many years ago. Yet, I think about the way she is not alone. Her fears are valid, and as I think about a career in medicine, I am acutely aware of this need for re-centering, placing care in the hands of community members, and mental health support groups. This rec-entering calls for an acknowledgement of the unique fear of being a Black woman in America and aim to provide justice in all sectors of life. So that in a time when hospitals are meant as locations that control illness, and mitigate risk, holistic care can come from outside of these institutions. To tackle the double waves that Black expectant mothers face requires an abolitionist framework. This is a method of unpacking trauma and terror that our country is more than ready for.

Notes:

Bailey, Moya. “Moya Bailey Bio.” Moya Bailey, 30 July 2018.

Moore JT, Ricaldi JN, Rose CE, et al. Disparities in Incidence of COVID-19 Among Underrepresented Racial/Ethnic Groups in Counties Identified as Hotspots During June 5–18, 2020 — 22 States, February–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1122–1126. DOI

Rankine, Claudia. “The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 22 June 2015.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Bridges, Khiara M. Reproducing Race: An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of Racialization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York : Grove Weidenfeld, 1991.

Mothers and Offspring Mortality and Morbidity Awareness Act: extends coverage for new mothers from its current standard of 60 days after childbirth to a full year of coverage.

Maternal Care Access and Reducing Emergencies Act: creates new grant programs that help deliver health care services to pregnant women and new moms.